The Yarmouth Collection

by Jessica David, Hamilton Kerr Institute third-year project

Painted around 1665 by an unknown though most likely Dutch artist, The Yarmouth Collection (Norwich Castle Museum) presents a lavish yet personal assemblage of objects once belonging to the Paston family of Oxnead Hall, Norfolk. Lingering beneath the guise of a somewhat innocuous table-top treasure, the pronk-vanitas still-life embodies the spirit of fleeting luxury, mirroring the Pastons’ dramatic reversal of fortune. Also known as The Paston Treasure, The Yarmouth Collection contains many of the symbolic devices found in seventeenth century pronk or pronk-vanitas still-lifes. The elegant arrangement of exotic foods and decorative objects are interspersed with sober reminders of mortality: a recently extinguished candle, a mirror without a reflection, several time pieces and dusty tomes stacked high on a forgotten shelf. Meanwhile, the African servant, monkey and grey parrot represent the exotic: symbols of status collected from distant locations, some pictured on the globe at the right of the composition.

|

||

|

The Yarmouth Collection, after conservation |

||

Perhaps the most striking characteristic of the painting today is its aggressively two-dimensional almost decoupaged quality. This is partly the result of fading and the loss of subtle mid-tones and partly due to choices made by the artist. Investigation of the artist’s materials and painting technique supplied some insight into the extensive degradation of the paint layer, which greatly impacts the colour balance and nuance of the composition. By re-tracing the artist’s creative process via reconstruction, intentional and incidental changes to the paint layer could be identified and recreated to give some impression of the painting’s original presence.

The Reconstruction

The present appearance of The Yarmouth Collection makes it a tempting subject for technical study, but the objective of the reconstruction extended beyond the desire to understand how it would have looked when freshly painted. It was hoped that a recreation of the painting process would offer an explanation for the extent and pattern of pigment degradation. As such, the area of reconstruction was strategically chosen to encompass areas of notable colour shift including the little girl at the foreground, the lobster, two nautilus cups and a Wan-li porcelain bowl, passages known to contain the light-sensitive pigments smalt, cochineal and yellow lake.

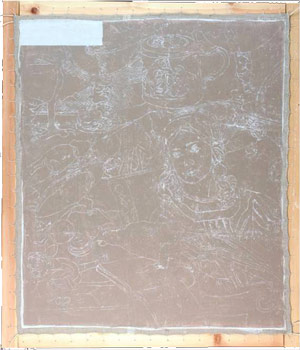

The first stage of reconstruction involved the making of a loom on which to stretch the canvas. A plain weave linen canvas of comparable thread count was selected as a good match for the original.(Fig. 1) Typical for the period, the canvas was sized with rabbit skin glue and primed with a mixture of lead white, chalk and drying oil. The canvas was then covered with a pinkish-gray ground or imprimatura similar to that on The Yarmouth Collection. It was fairly important to get the imprimatura colour correct, as it was intentionally left exposed in many passages of the original paint layer. A tracing of the original painting was transferred to the copy canvas with white chalk.

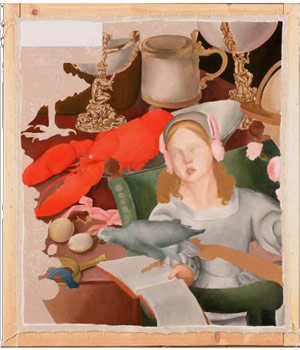

In keeping with traditional seventeenth century practise, each component of the composition was blocked in with a general ‘dead-colour’ comprised of fairly simple pigment mixtures.(Fig. 2) All pigments were ground on a glass plate in a linseed-based lead oil. The paint was applied with a small bristle brush and blended with a dry sable brush. Noimpasto work was employed at this stage: the paint was applied thinly according to the age-old ‘fat over lean’ rule.

|

||

|

Figure 1: Prepared, loomed canvas |

||

|

||

|

Figure 2: Dead colour blocked in |

||

|

||

|

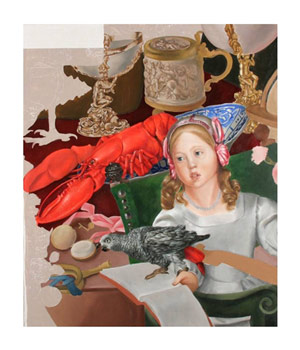

Figure 3: Working up |

||

In the next stage, known as the ‘working up’ process, greater attention was given to the three-dimensionality of each form. Shadows and highlights were added to the flesh tones of the little girl, and the parrot’s feathers were articulated with loose brushstrokes of azurite and ivory black. Based on technical analysis, an even glaze of cochineal mixed with a large proportion of chalk was applied to the lobster, save one claw (which was preserved for comparison). Pure cochineal was added to several other areas of the painting, all of which demonstrate some level of fading or discoloration, such as the tablecloth beneath the still-life, the gray parrot’s tail feathers and the little girl’s hair ribbons.

Final highlights and flecks of shadow were added to select areas of the reconstruction, to maintain a visual document of the painting process, Figure 3. Because of its virtuoso handling and notable discoloration, the lobster was brought to a high level of completion in the reconstruction. As projected, the process of reconstructing the lobster proved helpful in understanding its unusual pattern of degradation. The greyish hue of the lobster’s mid-tones is likely related to the large proportion of chalk mixed into the cochineal: added for its extending and handling properties. This is not the case with all areas of cochineal; in fact, final dabs of pure cochineal have retained their red hue though they have certainly lost some intensity with age.

Conclusion

The Yarmouth Collection bears testament to the aspirations and misfortunes of a fascinating family by documenting their diminishing collection of treasures and, even in its time-altered state, embodies the dizzying aesthetic of the pronk vanitas theme. The technical study and reconstruction of this complex painting have supplied a better understanding of its function, the artist’s working methods and the overwhelming opulence of its original appearance. Following its recent restoration at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, The Yarmouth Collection has returned to its home at the Norwich Castle Museum, Norfolk.